PHOENICS is a CFD oracle: it answers what-will-happen-if questions.

Or rather what may, even perhaps probably will, happen, in the light of current physical knowledge.

In these two sentences, much is implied, including:

To discharge these responsibilities, the user needs no specialist CFD knowledge; but the more he possesses the background understanding outlined in sections 3 and 4 below, the less likely he is expect more of PHOENICS, and indeed of CFD, than is reasonable.

For its part, when the PHOENICS oracle delivers its answer to the 'What' question, it ought, in order to give a balanced picture (and to maintain its credibility), to emphasise that the answer is based on a more extensive set of other if's than the questioner may have had in mind. The reason is that, in addition to the physical and geometrical parameters of the scenario in question, there are numerical parameters which may have an equally significant effect on the answer. If the user does not set them, PHOENICS uses its defaults, which cannot possibly be optimal for all circumstances.

These other if's fall into two classes, namely:

It is limitations in scientific knowledge which affect class a ; while those of class b are affected by limitations of financial resources; for computer time increases in proportion to the number of iterations; and to the number of computational cells much more steeply.

Cost takes on especial importance when this second mode of PHOENICS use is concerned. For its question is not "what will happen if?" It is rather: "of the range of possible 'if's, which will provide the most desirable 'what'?"

To answer this question requires the exploration of very many 'if' scenarios; so the cost per scenario must be kept to a minimum.

The words used for distinguishing the two modes differ in different communities. For example, heat-exchanger specialists call prediction 'rating', and optimisation 'design'. Others refer to the former as the 'direct' and the latter as the 'inverse' problem.

From the point of view PHOENICS, demoted now from 'Oracle to 'Simulation Slave', the only difference is that it has to work harder, in the second mode, before it is allowed to rest. One run more? one run less? PHOENICS does what it is told.

The first thing to emphasise is that the 'how' depends tremendously on the 'it'. To explain this essential idea, three extremely different prediction tasks will be discussed. The first is the calculation of the lift and drag forces sustained by an airplane in steady flight. The second is the determination of the adequacy of the ventilation of a car park. The third is the simulation of the flow of air, heat and pollution over a large urban landscape

The 'it' in this case is perfectly clear; but PHOENICS allows several possible answers to 'how?'. The question is: which of these best corresponds to its user's needs and capabilities?

(1) A user acquainted only with non-aeronautical applications of PHOENICS might suppose that it suffices to represent the airplane's shape by means of an stl file, its flight speed by upstream and downstream inlet and outlet objects, and its engine intakes and exhausts similarly; and then to choose a very fine Cartesian grid, into which the highly-non-Cartesian airplane would be fitted automatically by the easy-to-activate PARSOL technique. Then parallel-computing mode could be adopted so as to reduce the time needed to arrive at a converged solution. The following image shows an airplane in such a grid.

It is not a bad approach; and, if a very, very fine grid can be afforded, it ought to arrive at grid-independent values of the lift and drag. But its expense is very great; and even the finest affordable grid commonly fails to resolve adequately the all-important processes which take place in the thin boundary layer close to the airplane surface.

(2) Users of PHOENICS from before the years in which Virtual Reality became popular will remember that body-fitted-co-ordinate grids (BFCs), although more troublesome to create, can resolve the thin boundary layers very well.

Today's users need therefore to be positively advised that BFCs may be more cost-effective than PARSOL; and they should be provided with more assistance to create such grids to fit facet-described objects.

(3) Both Cartesian and BFC grids, in PHOENICS, are structured, with each grid node connected to six neighbours in the north, south, east, west high and low directions. This has its advantages in respect of ease of coding, and speed of computation; but its disadvantage is that it often causes too many cells to be placed where they are not needed. This is wasteful.

For this reason PHOENICS has been provided with an

unstructured-grid option. This is of the 'sub-divided-Cartesian' character which, to judge by modern trends, is agreed to be more cost-effective than the 'arbitrary-polygon' kind which was

fashionable in earlier years. It is commonly used in the aircraft industry.

(4) Lastly, an unusually knowledgable user might remind himself of the time before modern CFD existed, The aircraft designers recognised that, outside the boundary layer, the flow was inviscid and could be calculated by potential-flow theory; and that the effect of the boundary layer was to add to the airplane's volume a calculable 'displacement thickness'.

Why should he not use then, in combination, the PHOENICS potential-flow option for the main part of the flow and the also-in-PHOENICS 3D-boundary-layer option? How to do so is outlined in a power-point slide shown here.

(5) In summary, PHOENICS has many capabilities; but it does not yet:

In the future, perhaps; but not right now.

It must therefore be emphasised that simply to open the VR-Editor and choose from its menus seldom leads to the best way of using PHOENICS. Formulating precisely what it is to be used for and then seeking expert advice, is a better practice.

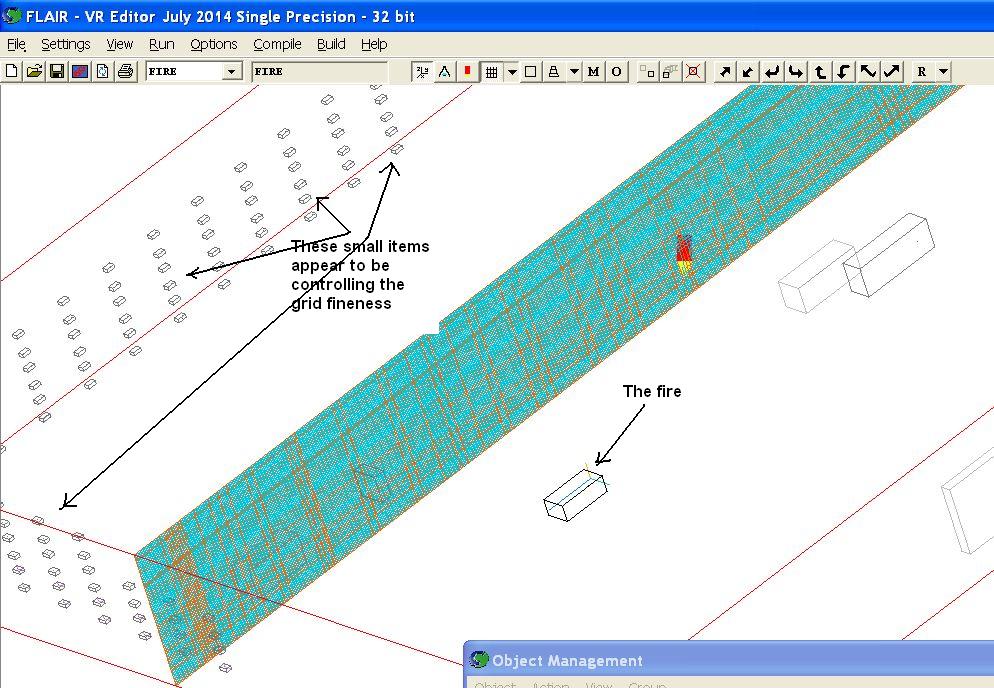

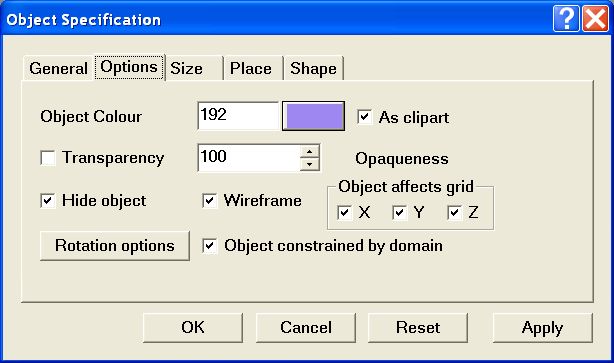

Items (b) and (c) render it unnecessary to strive for high numerical accuracy. The heat-production rate of the fire can be no more than a rough guess; turbulence models for buoyant flows are notoriously unreliable; and external atmospheric conditions, although probably influential, have also to be fixed arbitrarily.

It is therefore wise to use a coarse computational grid, so that computer times are short; for then many runs with varying boundary conditions can explore the significance of their uncertainty.

It is item d. which makes the problem in one respect more challenging to the user than the aircraft-drag one: he/she has always to extract from the information supplied to him/her the few items which are relevant to the question to be answered. This will have been done in the simulation shown below, which concerns the computed fire spread in a spirally-shaped car part in Annecy, France. Had it not been, the computations would have been immensely more expensive: but provided no better insight.

Among the benefits of restricting computer-run times to minutes rather than hours or days is that it allows exploration of influences otherwise ignored. For example, the strength and direction of the external wind must surely affect the movement of the smoke; both ought therefore always to be included in the list of variants investigated.

How to make the extraction? It depends on how the information is supplied.

Current development work at CHAM is directed towards making this coarse-grid representation a switch-on option. Meanwhile, users uncertain about how to make the change should ask CHAM's User Support.

PHOENICS is often used for making simulations such as that below, with a

streamline animation followed by a plan view of the grid.

It has to be said however that, although many hours of computer time may be spent, the reliability, and therefore usefulness, of the calculation often leave much to be desired.

There are several reasons for this, namely:

The following two diagrams illustrate the problem and one of its possible ameliorators. The one on the left shows how, in the absence of any physical difusion whatever, the default 'upwind difference scheme' of PHOENICS causes the 'pollutant plume' to spread. The second shows the reduced but still finite rate of spread when one of the many 'higher-order schemes' built into PHOENICS is activated.

The true result would be a thin band of contour lines, of constant concentration and unchanging width, stretching diagonally across the domain. Only one of the schemes can achieve this, the unique-to-PHOENICS CLDA scheme; and this is not accessible from the VR-Editor menus. None of them are switched on automatically; and few are ever used.

Aligning the grid with the wind-direction is also an alternative near-perfect solution; but only the Urban-Virtual-Wind Tunnel SimScene provides this automatically.

PHOENICS can be used successfully by persons of varied experience and background; however, the probability of success is greatest if they are already familiar with the general features of computer simulation of flowing continua; in particular, they should be aware of the following:

The ideal user of PHOENICS has been identified in this way in order that, should less experienced persons use it, they should have received due warning that computer simulations of fluid flow differ appreciably from calculations of the kind which are customary in, say, structural engineering or in rigid-body dynamics.

In the those fields, non-linearities are often of secondary importance, if indeed they are present at all; the computer code can therefore be left to produce the solution automatically.

Fluid-flow phenomena, by contrast, are essentially non-linear; so the user of a flow-simulating code must reconcile himself to having, on occasion, to help the code along, using his intuition and experience in the selection of the 'switches' and 'tuning knobs' of the solving procedure.

The final solution itself, i.e. the result of the solving procedure, of course must not depend upon the settings so chosen, any more than the scenery at the port of destination can depend upon the course which the ship's navigator selected.

It is WHETHER the solution is arrived at, and HOW SWIFTLY, that these steering adjustments may beneficially influence.

PHOENICS does already possess a primitive EXPERT system for making optimal adjustments of the numerical parameters as the calculation proceeds; and this auto-pilot feature is being further developed by CHAM. However what has been stated above remains true: the user of PHOENICS, or of any other CFD code, should never trust their predictions blindly, or expect them to proceed efficiently regardless of how injudicious are the user's settings.